Anthropology of the Heart

My Journey Through Anthropology to Animal Communication - Explore the soulful practice of animal communication, fostering understanding and harmony between species. Discover intuitive techniques and resources that deepen connections with animals, birds, and nature. Join us on a journey towards healing and oneness, embracing earth-wisdom and spirituality in every interaction.

5/8/20244 min read

When asked what marks the beginning of civilization, most would say tools. Or fire. Or the first stone temple.

But anthropologist Margaret Mead had a very different answer:

“A healed femur.”

Because in the animal world, a broken femur is fatal.

You can’t run. You can’t gather food. You can’t defend yourself.

If someone survived a broken femur, it meant another stopped, stayed, and cared.

Not for gain. Not for duty.

But simply — because they chose compassion.

That, Mead said, is civilization.

I first encountered Mead’s story during my undergraduate degree in Anthropology — a time when I was beginning to ask deeper questions:

What is culture, really?

What is intelligence?

What separates us from other beings — humans, animals, nature… and what unites us?

Those years were filled with names that would go on to shape my life in unexpected ways: Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, Madhumala Chattopadhyay.

Each of them, in their own way, dissolved the boundary between study and soul.

“The purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences.”

— Ruth Benedict

This quote struck me like a lightning bolt the first time I heard it. It still does.

Because what if the goal of understanding culture — any culture — isn’t to dissect or define it… but to honor it?

To make space. To protect difference, not erase it.

Years later, when I began communicating with animals, I realized that same applies.

Be it a remote tribe, a wild elephant, or a street dog — the moment you assume superiority, you’ve already stopped listening.

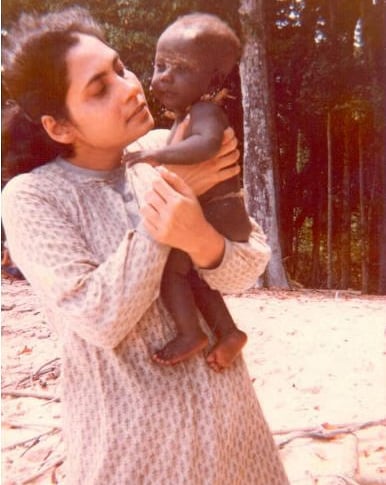

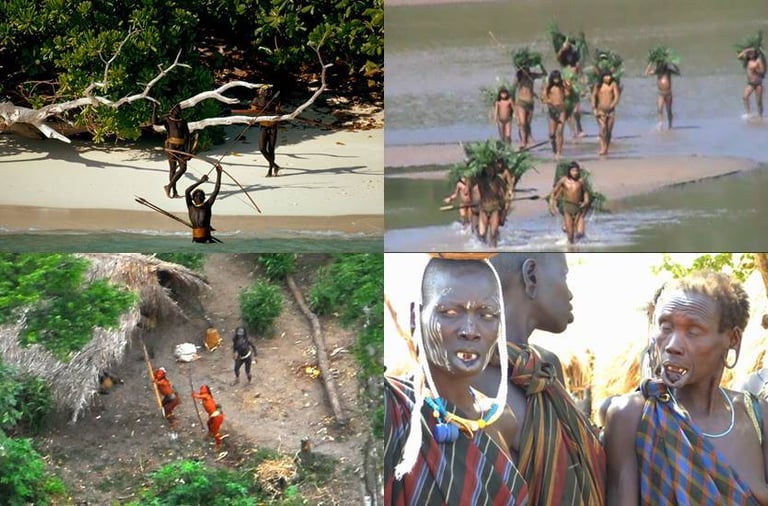

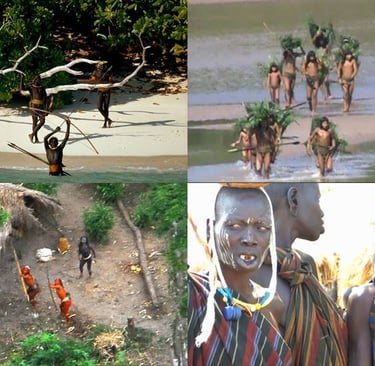

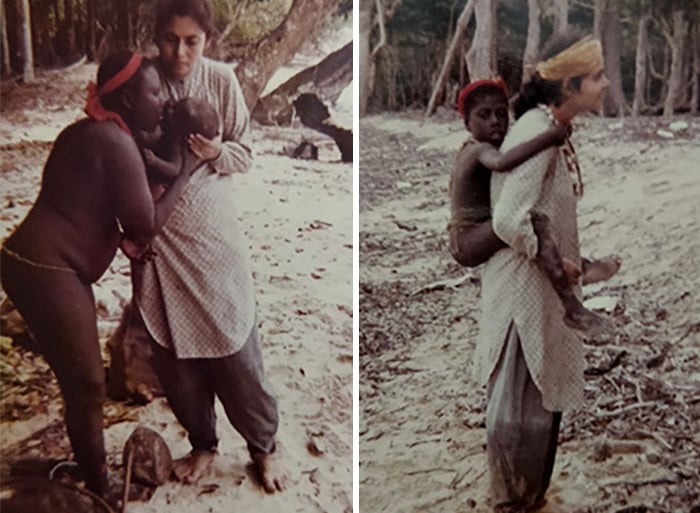

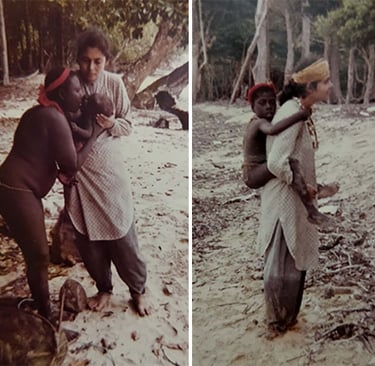

Madhumala Chattopadhyay was the first woman outsider to make contact with the Sentinelese — a tribe that has lived in isolation for over 60,000 years on North Sentinel Island.

Every previous attempt had ended in hostility or tragedy. But Madhumala’s presence shifted something.

On one visit, a young man raised his bow toward her — and a Sentinelese woman stepped forward and gently lowered his hand.

Later, Madhumala and her team waded waist-deep into the sea, offering coconuts — not as scientists claiming territory, but as guests, mindful of whose land they were entering. The images from that encounter told a different story: one of quiet recognition, not conquest.

But it was her reflection afterward that struck me most:

“You feel that you are there to study them, but actually, they are the ones who study you.

You are foreign in their lands.”

That single line stayed with me.

It held the essence of what I would later come to understand through animal communication:

That presence matters more than power.

That respect is the first language.

Madhumala didn’t seek to dominate or define. She listened. Observed. Honored. She shared how, in all her years of working alone with the tribes of the Andamans, she was treated with dignity and care. “They might be primitive in technology,” she noted, “but socially, they are far ahead of us.”

And though she could have built her career on those historic encounters, she chose restraint. She actively discouraged further contact with the Sentinelese — not out of fear, but out of deep respect.

“Their troubles started after they came into contact with outsiders,” she warned. “The tribes don’t need outsiders to protect them — what they need is to be left alone.”

That taught me something essential.

It isn’t our job to fix another culture, another species, another way of life.

It’s our responsibility to understand — and then to step back.

To recognize that honoring someone’s space — be it human or animal — is a form of love.

To accept that listening, without intrusion or agenda, is enough.

And to know that sometimes, the most compassionate thing we can do… is to let them be

Madhumala Chattopadhyay — The woman who made the Sentinelese put their arrows down.

This, I have discovered through animal communication, extends beyond humans.

Whether I’m connecting with a grieving pet, a wild creature, or a tree that’s been standing for centuries — I approach not as a “professional” with tools.

But as a presence. As one soul meeting another.

Because empathy isn’t a soft skill.

It’s an evolved intelligence.

It’s the glue that binds societies, species, and ecosystems together. To me, animal communication is not some mystical gift — it’s a remembering - A natural extension of being more of yourself.

It’s anthropology of the heart.

It’s Jungian integration in real-time.

It’s listening the way our ancestors once did, before language became a wall.

Through years of practice and deep communion, I’ve come to see animal communication as a tool for harmony — a way to dissolve the illusion of separation between humans, animals, and nature.

Because when you truly understand another being — not to control them, but to know them — hostility fades.

Fear dissipates.

In its place arises peace. Compassion. Love.

I invite you to join me on this path. A choice toward love. Toward connection. Toward peaceful coexistence with all life. Because, after all

we’re all just walking each other home.

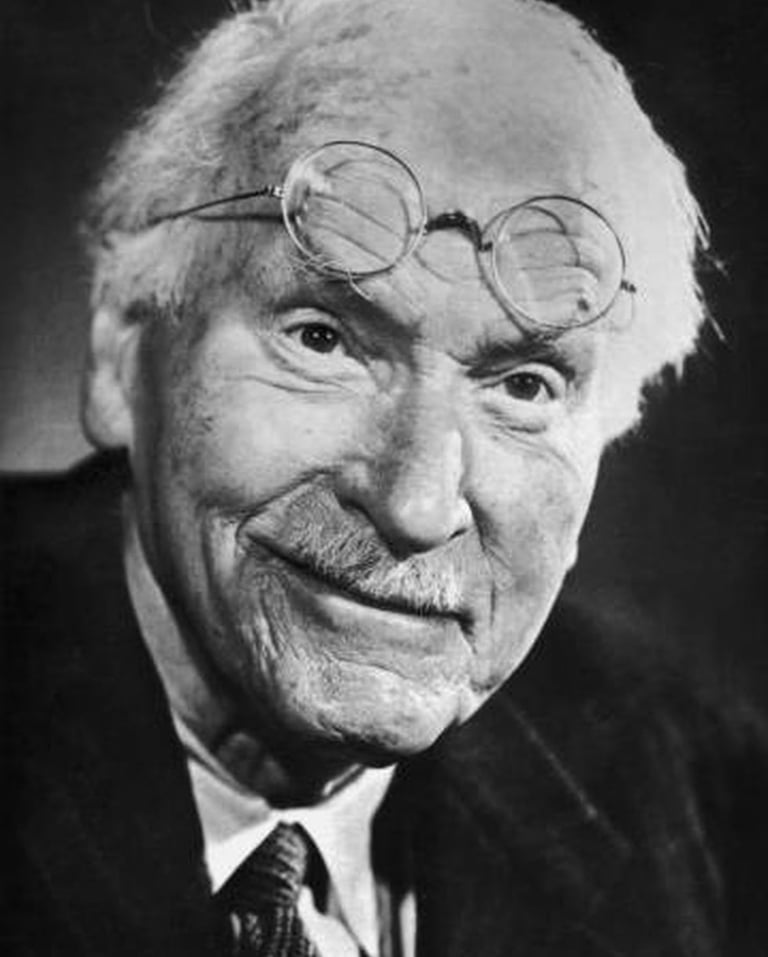

Around the same time I was studying anthropology, I also began exploring the works of Carl Jung.

Jung didn’t view the soul as something to be analyzed, but as something to be remembered.

He wrote:

“Know all the theories, master all the techniques, but as you touch a human soul, be just another human soul.”